medpundit

|

medpundit |

||

|

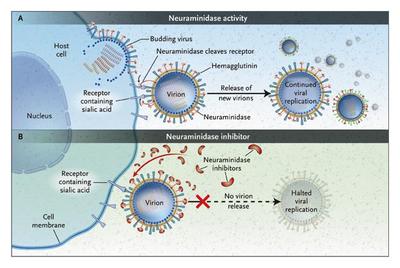

Monday, October 10, 2005The time from exposure to the development of symptoms (the incubation period) ranges from 2-8 days. The illness usually begins with a high fever and a cough. It may also be associated with diarrhea and vomiting, unlike the typical case of human influenza which is strictly a respiratory illness, and which usually begins as a high fever and a runny nose. The cough may progress to shortness of breath, respiratory distress, and ultimately respiratory failure. The progression from fever and cough to respiratory failure usually takes about a week. Unlike regular human influenza, death from avian influenza occurs as a result of the virus directly injuring the lung cells. (In normal human influenza, death is usually due to a secondary infection on top of the flu, not from primary damage caused by the influenza virus). It's always scary to deal with a virus that is capable of doing so much damage so quickly. Luckily, it isn't very contagious: To date, the risk of nosocomial transmission to health care workers has been low, even when appropriate isolation measures were not used. However, one case of severe illness was reported in a nurse exposed to an infected patient in Vietnam. What has the worriers worried is that there's a potential for the bird flu virus to mutate just a little and cause it to do two things: 1) easily infect people and 2) become more contagious. The Avian influenza virus belongs to the same virus family as regular human influenza A - the orthomyxoviruses ("myxo" means "mucous," so they're aptly named). They are siblings rather than cousins. They are both Influenza A- type viruses, meaning they have similar qualities in their genetic material (the RNA) and in the proteins that make up their outer coats, both shown vividly in these electron micrographs. The "A" influenza viruses are further broken down by the structure of two of the proteins that make up their outer coat - hemagglutinin (H), which helps the virus bind to a host cell, and neuraminidase (N), which helps new virus particles cut loose from the infected cell at the end of their replication cycle. The two types of human influenza A that routinely make their way through the world each year are influenza A(H1N1) and A(H3N2). The bird flu is influenza A(H5N1).  These two proteins are vital to the life cycle of the virus. When a virus infects a cell, it first binds to the cell's outer membrane using its hemagglutinin. Then, it fuses with the cell, releasing its genetic contents into the cell's interior. There, the virus's genetic material, in this case RNA, replicates within the cell. New virus particles are then assembled using the virus RNA inside the cell. The new virus particles fuse with the inner cell membrane and are released back into the outer world when the neuraminidase clips the binding hemagglutinin receptor. The new virus particles then go on to infect more cells, or to be coughed up or sneezed out into the greater outdoors. Tamiflu, the drug mentioned most as a possible treatment for bird flu, is a neuraminidase inhibitor. It prevents the new virus particles from leaving their host cells. It doesn't prevent them from getting in, which is why most people who use Tamiflu for the flu are still sick. It just prevents them from going on to infect more cells - which is why it usually just shortens the course of the illness. Timing is everything when using Tamiflu - you want to get the drug into the body before the virus has gone through too many replication cycles - which is why it has to be given within the first 24 to 48 hours of illness to be effective. How effective it is against the bird flu is anyone's guess, but it's probably better than nothing. Virologists have been keeping an eye on the bird flu since 1997. They know that it has a variation in its hemagglutinin protein that makes it very easy for it to cut loose from cells on its rebirth (it doesn't even need to rely on its own neuraminidase, but can use enzymes from the cells it infects), that it is very efficient at replicating, and that it has a mutation that makes it resistant to the host cell's immune system. They also know that the virus keeps evolving and mutating as the years go on. What they don't know is whether or not its next evolution will make it more or less dangerous for man. Their job is not unlike the men and women of the National Weather Service who spend their days watching tropical storms and trying to determine when and if they'll become a hurricane, and where, if, and when they'll hit land. The virologists, however, are working with a lot less information. A virus is a lot less predictable than a hurricane. posted by Sydney on 10/10/2005 08:49:00 PM 1 comments 1 Comments:I have the pleasure to visiting your site. Its informative and helpful, you may want to read about obesity and overweight health problems, losing weight, calories and "How You Can Lower Your Health Risks" at phentermine site. By , at 2:33 PM |

|